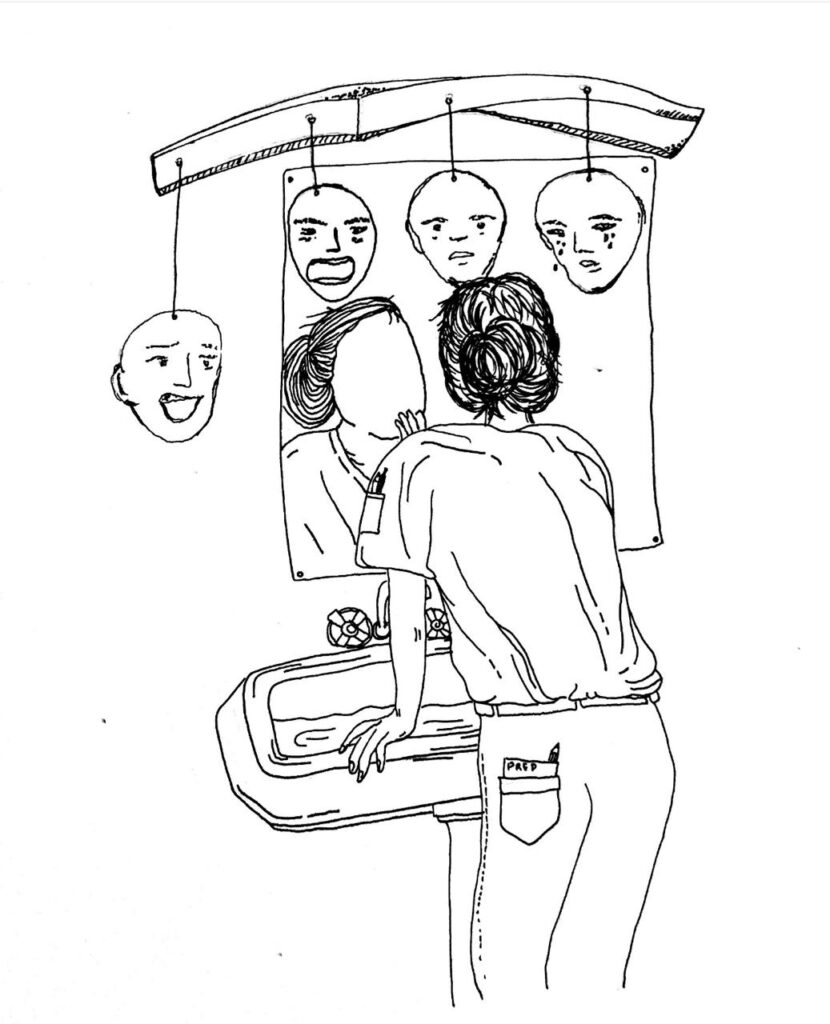

Story by Andy Fenner. Illustration by Caro Gardner.

You only need a passing knowledge of cooks’ biographies like ‘Kitchen Confidential’, or a few shifts in a busy eatery to know that restaurant kitchens can be a gateway to wild parties with their sidecar of substance abuse. The pressure-cooker stress of mad shifts and crazy co-workers can also aggravate or initiate mental health issues. Andy Fenner sat down with a couple of battle-scarred chef friends for a frank chat about ‘the life’.

Rock bottom is different for everyone. For Dave Schneider, it was on his knees, with a gun barrel pushed into the back of his head.

“I’d spent the evening drinking and snorting everything put in front of me,” Dave explains. He found himself wandering around Cape Town and was kidnapped by a bunch of gangsters. They drove him around for a while, then led him into a house where they made him smoke “something weird”. Eventually they led him out to a field, cocked a pistol and forced him to his knees.

He “started saying goodbye” but – for whatever reason – they just walked away. Dave made his way towards the closest lights he could find. No phone. No wallet. No. Fucking. Shoes.

Fast forward a few years and the guy is an inspiration. Spearheading one of the country’s best restaurants (Chefs Warehouse at Maison in Franschhoek). He’s a big dude. Like, professional-rugby-player big. And that’s what he wanted to do for a big chunk of his life. That was his path. But a severe neck injury forced him into a Plan B. Bad news for rugby fans. Good news for anyone who’s ever tasted his cooking.

Dave is now a recovering alcoholic. The type who looks you in the eye when he tells you. No apologies. Apart from running an impressive eatery, he’s doing impressive work outside of the kitchen. He’s heading up a local movement of young chefs, no longer interested in the drug-booze-binge-repeat model of kitchen brigades.

Recently I had the chance to sit down and share a table with Dave, as we discussed mental health, coping mechanisms, anxiety disorders, the industry and more. Said table was inside SHIO, a beautiful restaurant owned by the enigmatic Cheyne Morrisby. Cheyne had also volunteered to “get real”, as we swapped stories about burnout, addiction and trying to balance family life.

A lot of people know Cheyne. Or think they do. The truth is, they know his work. They know his restaurants. But Cheyne Morrisby? Who is he? Like, really?

Cheyne opened up about cooking in a professional kitchen from the age of 16. With a broken and abusive family life, it was the kitchen that provided him with what he needed most at the time. Structure. Support. Camaraderie.

“And an escape.”

The theme of escapism is something I see repeatedly in our industry. That, and addiction.

“It’s the same thing, really”, Cheyne explains. “We sacrifice so much. Friends, family, a normal life. Everything. But we still don’t want it to stop. We need to constantly remind ourselves of why we are even doing this.” He says this with a shrug, as if he is trying to get the answer from somewhere inside his own head.

Almost 20 years ago, Cheyne found himself head chef of Blues Restaurant, back when Blues Restaurant was…well…good. Cheyne was running the show. Crushing it on the pass, handling suppliers, overseeing staff, combing figures and spreadsheets. And the dude was doing it all in his early 20s. Full of confidence, he headed abroad to explore. He felt untouchable.

Until he imploded.

His first gig saw him working the fish section at Quaglino’s, a signature brasserie in St James, London.

“I was young and arrogant. I kept thinking: what the fuck are they doing putting me on such a basic job?”

Then he made a mistake. And another. And another. Plates were hurled. Insults rained down with the shards of shattered porcelain, as the head chef cursed and spat vitriol. Cheyne felt that confidence ebbing.

“I finished my shift, got in the tube and broke down. I cried all the way back to my digs. But the next day I got up and did it again.” What followed was an extended stint in London. Not only did he survive (and thrive) in that tough kitchen. He got to explore the scene. It was this exploration that allowed him to fall in love with pan-Asian flavours. It was exciting, and the buzz of discovering ingredients he’d never even seen before made the savage pressure and steep learning curve worth it.

“I wouldn’t change anything,” he says, with the self-assurance that only someone who has been through something like that can muster.

When Cheyne came back to South Africa, he immediately set about creating a space to unleash his new-found skills. It eventually came in the form of a tiny, hole-in-the-wall in Bree Street, way back before anything much was happening on Bree. I know, because I sat in that little space often. It blew me away.

I don’t know if I knew back then how much Cheyne was to impact my food writing, but he did. The guy was cooking some of the bravest food I had seen locally, but it was the way he did it that stuck with me: Flying solo in a small room with an open-plan kitchen and a communal table. Small plates. Big flavours. No chef jacket. No waiters. No frills. No bullshit.

It was so incredible, we even threw a surprise birthday party for my wife at that tiny venue. Almost 10 years ago, and I can still remember some of the dishes. Thing is though, Cape Town wasn’t ready. Pretty soon after launching, he was forced to close.

“By the end of it, I was exhausted. I was doing a lot of coke. We would have a few beers and a few tequilas after work regularly. I was just miserable. I couldn’t wait to close the doors,” he ex-plains.

I can relate. Having struggled with my own drug and depression issues, I know that the easiest time to do either of those things is when things start getting bad. You rationalise it and you justify it. You lie to yourself first, then you lie to your loved ones. It’s like a slow cloud that envelopes you. Like a sugar cube that you put under your tongue, hoping it won’t dissolve. Of course, it will. It always will.

The problem with this behaviour, is that you probably don’t even realise you’re doing it. It’s habitual. You can only really stop the rot if you change your thinking first. And if you have the ability to detach yourself from those thoughts. But thinking – and overthinking – is a curse that a lot of chefs struggle with. The constant search for validation, for recognition and for the next level of “success”. (Whatever that means; is it a plate that you frame and put on your wall? An extra star? An extra hat?) Who knows?

I push for more from two men I admire greatly. The feeling at our table is that we all have common threads and overlaps. And we do. But how do we pull at these, to try and make some sense of it all? How do we take what we have all learnt and help others with it?

“The industry needs to understand balance,” Dave offers up. “As a young chef, I would push my-self until I could hardly stand up. But then I’d hit the bars and pubs and drink until I blacked out. I had a bed and a room but I hardly spent any time there. I began using work as an excuse to par-ty.”

What I am trying so hard to understand is how do we change this? How do we educate an entire generation about the toxicity that bleeds through so many professional kitchens? How do we drive home the importance of mental health? How do we take a young kid and explain the significance of meditation and healthy eating and…just fucking sleeping for more than two hours a night?

The answer seems ridiculous.

“We tell them,” Dave says, smiling.

“We show them,” Cheyne says.

I agree with this. There is a responsibility that falls on people like Dave, Cheyne and myself. There is a responsibility that falls on anyone who has hit rock bottom or has watched something burn to the ground, before trying to fix it. But we don’t need to wait for that to happen. We can see the car screaming towards the wall and we can prevent it. We can. But all of us need to begin talking. We need to admit insecurities and vulnerabilities. We need to. And we have to.

It’s been an emotional meeting. Raw. Honest. Enlightening. We step outside and say our good-byes. Cheyne is distractedly checking a wine glass sample that one of his team has brought over. He is opening The Piano Bar (next door to where we are sitting) the following day and he has a lot on his mind.

It’s a building site. Dust everywhere. Drilling. Sanding. Sawing. A bit of a shit show. I turn and leave, with a smile on my face. All three of us are exactly like that site. A work in progress. Cheyne will turn that shit show into something beautiful. And with a few changes, I know this industry could do the same for each of us.

If this article resonates with you, in any way, please do something about it. Reach out. You do not have to do this by yourself. Being in this industry is supposed to be a gift. If it feels like a burden, you are already in trouble. Admit to yourself that you need help and then GO ASK FOR IT. Colleagues, family, friends. Anyone. Depression is a very slippery slope. You need to understand environmental factors (who do you hang with, what are your habits?). You need to understand biological factors (what is your predisposition? What DNA quirks do you have?) You need to understand chemical factors (what is your brain makeup? How are you “wired”?) It’s complicated stuff and these issues are things I wrestle with every day. I wish I had someone to hold my hand and show me these things 10 years ago. But I am finally finding answers. Reach out to us on mindthegap@broth.com and let’s see if we can help you to do the same.